I made these Microsoft Excel charts to compare the Blue Jays' seasons (to be updated after each successive season).

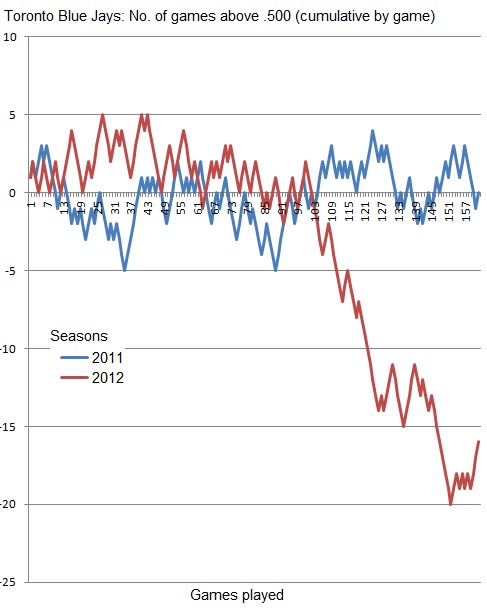

The 2011 and 2012 seasons were managed by John Farrell. Note the 2012 team's steady slide after game 100, soon after Bautista went on the DL for most of the rest of the season. John Gibbons will manage for 2013.

Below: Wins.

Below: Winning percentage.

Below: Games above .500.

Below: Winning percentage by season, from the team's inception. Note the decline after their World Series wins in 1992 and 1993.

Friday, December 14, 2012

AL East team stats (2012 season)

Here are some MLB-related charts that I made using Microsoft Excel, showing and comparing each American League East team's 2012 season wins, winning percentage, and games above .500.

Below: Wins.

Below: Winning percentage.

Below: Games above .500.

Below: Wins.

Below: Winning percentage.

Below: Games above .500.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Toronto Mayor Rob Ford’s ouster was legally dubious

Update (Dec. 18, 2012): Added clarifying final paragraph.

For speaking and voting on a matter in his pecuniary interest, actions which contravened Section 5 of the Municipal Conflict of Interest Act, R.S.O. 1990 (MCIA), the seat of Toronto Mayor Rob Ford was declared vacant by Justice Charles Hackland in a November 26, 2012 decision, Magder v. Ford, 2012 ONSC 5615. Whatever the merits of the rest of Hackland's finding, he seems to have misjudged the application of s. 4(k) of the MCIA, and therefore vacated Ford's seat improperly.

Ford was held to have violated s. 5(1)(b) when he spoke and voted on a matter involving the personal repayment of the sum of $3,150 arising from improper use of city government letterhead to solicit donations for his charity, the Rob Ford Football Foundation.

Section 5 of the MCIA reads:

When present at meeting at which matter considered 5. (1) Where a member, either on his or her own behalf or while acting for, by, with or through another, has any pecuniary interest, direct or indirect, in any matter and is present at a meeting of the council or local board at which the matter is the subject of consideration, the member, (a) shall, prior to any consideration of the matter at the meeting, disclose the interest and the general nature thereof; (b) shall not take part in the discussion of, or vote on any question in respect of the matter; and (c) shall not attempt in any way whether before, during or after the meeting to influence the voting on any such question.Section 4 of the MCIA provides for exemption from s. 5 under certain circumstances; Ford has appealed to clause k, which reads:

Where s. 5 does not apply 4. Section 5 does not apply to a pecuniary interest in any matter that a member may have, . . . (k) by reason only of an interest of the member which is so remote or insignificant in its nature that it cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to influence the member.Hackland's denial of s. 4(k)'s applicability reads:

While s. 4(k) appears to provide for an objective standard of reasonableness, I am respectfully of the view that the respondent [Ford] has taken himself outside of the potential application of the exemption by asserting in his remarks to City Council that personal repayment of $3,150.00 is precisely the issue that he objects to and delivering this message was his clear reason for speaking and voting as he did at the Council meeting. The respondent stated, in his remarks at the Council meeting, "[A]nd if it wasn't for this foundation, these kids would not have had a chance. And then to ask for me to pay it out of my own pocket personally, there is just, there is no sense to this. The money is gone, the money has been spent on football equipment…." In view of the respondent's remarks to City Council, I find that his pecuniary interest in the recommended repayment of $3,150.00 was of significance to him. Therefore the exemption in s. 4(k) of the MCIA does not apply.Although Hackland does agree that Ford's pecuniary interest ($3,150) was quantitatively insignificant, describing the sum as "modest" (paragraph 48) and recognizing "that the circumstances of this case demonstrate that there was absolutely no issue of corruption or pecuniary gain on the respondent’s part" (paragraph 48), he believes that the mayor's remarks nevertheless prove it "was of significance to him". Yet these remarks, which are quoted in the decision (e.g., "And then to ask for me to pay it out of my own pocket personally, there is just, there is no sense to this"), combined with Ford's status as a millionaire and Hackland's admission that the monetary figure was trifling, suggest that the mayor was motivated not by the monetary amount, but by principle—thereby nullifying the quantitative significance of his pecuniary interest. Moreover, the justice reports that Ford testified that he believed he did not owe the funds (paragraph 51), which is further evidence that Ford was voting on principle, not for personal monetary gain. The mayor's testimony that he understood conflict of interest to be a situation in which ". . . a member of council must benefit" ("Rob Ford out: Mayor's attack dog Mammoliti quits top committee", Toronto Star, Nov. 26, 2012) is consistent with his voting against a repayment that he regarded as unjust rather than financially onerous. If the issue were indeed one of principle to Ford, his pecuniary interest per se would be insignificant, and s. 4(k) would apply, thus sparing him from the otherwise "mandatory removal from office for contravening s. 5(1) of the MCIA", which, Hackland writes, "is a very blunt instrument and has attracted justified criticism and calls for legislative reform" (paragraph 46). Furthermore, Hackland's decision interprets s. 4(k) out of existence. Section 5(b) already applies because Ford voted, and it is logically true that a voter has a preference with respect to the matter voted upon. This preference must be, by the exclusive either-or nature of voting, an implicit objection to the other possible option(s), in this case the demanded repayment. Ford's statements as quoted by Hackland simply show what is necessarily true by virtue of the fact that Ford voted. Of course Ford objected to repaying the money donated to his charity; this is apparent from his voting behaviour even if he had said nothing about it. Thus, Hackland's identification of the rationale for Ford's participation in the vote is no more than circular reasoning about voting. Hackland concludes, in effect, that the s. 4(k) exemption does not apply because Ford voted—without noting or understanding the obvious point that the act of voting itself implies significance to the voter. That Ford voted cannot nullify s. 4(k), because s. 4(k) can only apply because he voted. Hackland's broad interpretation of s. 4(k), in which he conflates "significant pecuniary interest" with the motivation to vote—rather than with monetary quantity—cannot be correct, for it would negate every appeal to the s. 4(k) exemption as it pertains to s. 5(1)(b) (it being impossible to divorce the desire to vote from the act of voting), rendering s. 4(k) automatically null whenever the member has voted—in plain contradiction to its inclusion in the MCIA. To Hackland, in other words, a vote can be insignificant to the voter. Such a voter would be indifferent to the outcome, despite the paradox this presents. He seems to think that s. 4(k) is meant to apply only to a voter who lacks a preference. In fact, no such voter can exist, for voting is proof of a preference that is significant enough to motivate the voting act. In short, a vote itself proves significance, of which s. 5(1)(B) already takes account, and therefore s. 4(k), which can only apply when s. 5(1)(B) has been violated, cannot be denied on this basis. Ford's remarks, which only prove the significance of his desire to vote (as opposed to significance of the monetary quantity), were thus redundant insofar as they echoed what his vote expressed, and exculpatory insofar as they point to his vote as a principled defence against perceived unfairness, instead of as monetary aggrandizement.

Labels:

Rob Ford

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)